Poblet Monastery in Catalonia – withdrawing from the world

A whippet wind and oddly washy sky were badgering us out of Barcelona on the day of my birthday, as we wended west, heading for Poblet Monastery. Life in an amped city like Barcelona doesn’t offer many moments of quietude, and as General Election day collided with the last shopping weekend before Christmas, both my friend and I were up for sallying out of the city and taking in one of Catalonia’s most awe-inspiring UNESCO World Heritage sites.

The 12th-century Royal Monastery of Santa Maria of Poblet sits much closer to Tarragona than Barcelona – about an hour and a half’s drive west from the Catalan capital and just past the medieval walled town of Montblanc. It’s one part of a trinity of Cistercian monasteries in Catalonia known collectively as the ‘Cistercian route‘.

The Cistercian Order of monks and nuns was a very big deal in Catalonia, leaving a legacy of spiritual centres straddling several Catalan comarcas (regions). Inspired by a group of Benedictine monks who founded a monastery in the French village of Cîteaux at the very end of the 11th century, the Cistercian monks established Poblet Monastery less than 60 years later, in 1151.

As the car trundled west, past parched countryside of wheat fields and vineyards, I knew none of this. In truth, I’d had to google ‘Cistercian’. The concept of an anchoritic existence fascinates me, though, and as I read online reviews on the way there, I started to become more and more intrigued by the history of this place, so pivotal to the story of Catalonia itself.

Work, pray, love

From medieval times to the modern day, being a Cistercian monk means adhering to an austere set of principles, summed up by the pragmatic and pithy imperative of ‘Ora et Labora’. Whether it was in the kitchen, in the chapel, in the library or toiling in the various vineyards that flank the surrounding countryside, the resident monks inside the large fortified complex had to function as a self-sufficient community. (The nearby fields were a great source of income for the monastery, whose agricultural estates were something of a 12th-century economic powerhouse – the vineyards still produce Conca de Barberà-denominated wines to this day.)

From monastic to monarchic

My friend and I had booked on to a guided tour (in Spanish rather than Catalan on my account) led by a kind-eyed guide who showed us round the surprisingly large complex in around 40 minutes.

The monastery went from strength to strength over the early centuries, she explained, and although historians aren’t sure how many monks would have lived here in the abbey’s heyday, around 130 men seems to be the consensus. Monks mingled with ‘religiosos’, who had a lesser monastic ranking, and were not bound by the same strict rules of observance, scribing duties or regimen of prayers.

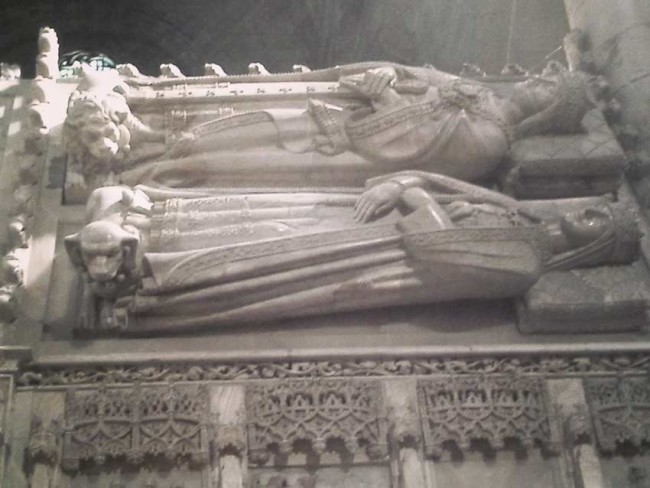

Aside from being one of the largest and best-preserved Cistercian abbeys in Europe, Poblet’s prestige comes from its former status as the official royal sepulchre of the monarchs of the Crown of Aragon. Kings, queens and infant members of the royal household were all buried here, in alabaster tombs arching across the church’s transept like chess pieces just waiting to be picked up and played.

I was transfixed by the figures of animals sculpted as companions at their feet – lions for the kings and queens for the dogs – and was particularly intrigued to see a long-lugged canine that resembled my own Cocker Spaniel cradling one queen’s toes.

Calamity in the cloisters

Stepping from the church to the refectory, the herb garden to the former dormitory, the barber’s room to the only designated speaking space in a stone-cold corner, our little group was told how a calamity finally befell the monks’ cloistered way of life in 1835. The then Spanish Prime Minister, gung-ho revolutionary liberal Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, led the campaign to privatise and seize church lands across Spain, in what was called the ‘Ecclesiastical Confiscations’ (‘desamortizacion de Mendizábal’).

Riled up on anticlerical rhetoric, angry mobs moved in, looting the library of historic treasures and torching various parts of the monastery. Their lands repossessed and their lives endangered, the resident Cistercian order had no choice but to evacuate.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that the ruins of Poblet Monastery began to be restored, and in the 1940s it received a fresh monastic purpose as it welcomed four Italian monks chosen to refound the site.

Today, the resident community of so-called ‘white monks’ numbers 32, and their daily cloistral routine dictates the running of the monastery as a tourist attraction. The site is closed between 12.30 and 3pm each day, for example, as the monks eat lunch in silence at the long wooden benches of the refectory, while one reads scriptures in Catalan from the pulpit.

Although it is possible to get there by public transport from Barcelona, a much more straightforward option would be to hire a car, and make sure to plan your trip around the opening hours explained on the official website. You’ll be glad you made the effort.

Follow @guirigirlbarca on Twitter

Guiri is one of those words, like feminist or peely-wally, that I want to reclaim. Locals use it to refer to tourists - you know the ones - who stick out a million miles. No matter how long I live in Barcelona, that's always going to be me. (P.S. While Barça locally refers to the football team, Brits use Barca as shorthand for the whole city.)

Guiri is one of those words, like feminist or peely-wally, that I want to reclaim. Locals use it to refer to tourists - you know the ones - who stick out a million miles. No matter how long I live in Barcelona, that's always going to be me. (P.S. While Barça locally refers to the football team, Brits use Barca as shorthand for the whole city.)

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks